- Ritesh Malik

- Posts

- can’t sell. won’t sell.

can’t sell. won’t sell.

this is about emotional attachment overriding economics

Last month, my best friend's uncle asked me to review his finances.

He's 68, diabetic, and his hospital bills keep climbing.

His wife needs a hip replacement that'll cost ₹8 lakh. They're taking loans to cover medical expenses (yes, they didn't get insurance early on).

Then I looked at his assets.

He owns a 2,000 sq ft property in Mumbai's Bandra worth ₹10 crore. Fully paid off. Prime location. Developers call him weekly with offers.

I suggested selling it, moving to a smaller apartment, and keeping ₹7-8 crore liquid for healthcare, investments, and his grandchildren's education.

His response stopped me cold.

The property generates zero rental income. Sits mostly empty since his kids moved abroad.

Meanwhile, he's borrowing at 12% interest to pay medical bills rather than access the ₹10 crore sitting in bricks and mortar.

That's when I started seeing this pattern everywhere. And realized India isn't just dealing with an economic problem. We're trapped in a psychological cage worth trillions.

The discovery that really opened my eyes came from BSNL and MTNL's balance sheets.

BSNL has a debt of ₹23,297 crore as of November 2024.

MTNL owes ₹24,000 crore in bonds plus ₹1,600 crore in defaulted loans.

These companies sit on prime real estate across India. The Department of Investment and Public Asset Management approved the monetisation of BSNL's assets worth ₹18,200 crore and MTNL properties worth ₹5,158 crore.

After years of trying, BSNL has earned ₹2,387.82 crore and MTNL ₹2,134.61 crore from land and building monetization up to January 2025. That's roughly ₹4,522 crore out of ₹23,358 crore in approved assets: about 19% monetized despite massive debt burdens.

This isn't bureaucratic incompetence.

In 1990, Daniel Kahneman gave Cornell students coffee mugs. Then asked mug owners what they'd sell for, and non-owners what they'd pay.

Identical mugs. Sellers wanted $7. Buyers offered $3.

The phenomenon has a name: the endowment effect. We systematically overvalue things we own, not because they're worth more, but simply because we own them.

Brain imaging studies show why. When you consider selling something you own, your right insula activates. That's the region associated with anticipating pain. Your brain literally processes letting go of possessions as a threat.

This made sense for our ancestors. Carelessly losing survival resources meant death. But in modern India, this same wiring is strangling economic growth.

I started tracking how this plays out across India.

Indian households hold 25,000-27,000 tonnes of gold. That's ₹160 lakh crore worth. More than the combined reserves of the world's top ten central banks.

The government offers 0.5-2.5% interest schemes to monetize this gold. Only 6% of households even know these programs exist.

Meanwhile, India imported approximately $72 billion worth of additional gold in FY 2024-25. We're buying more gold while the gold we already own sits idle in lockers.

This isn't about gold's value. It's about emotional attachment overriding economics.

My mother has jewelry from her grandmother she's worn exactly twice in 30 years.

Market value? Maybe ₹15 lakh. Her valuation when I suggested selling it? "Priceless."

The pattern extends beyond gold.

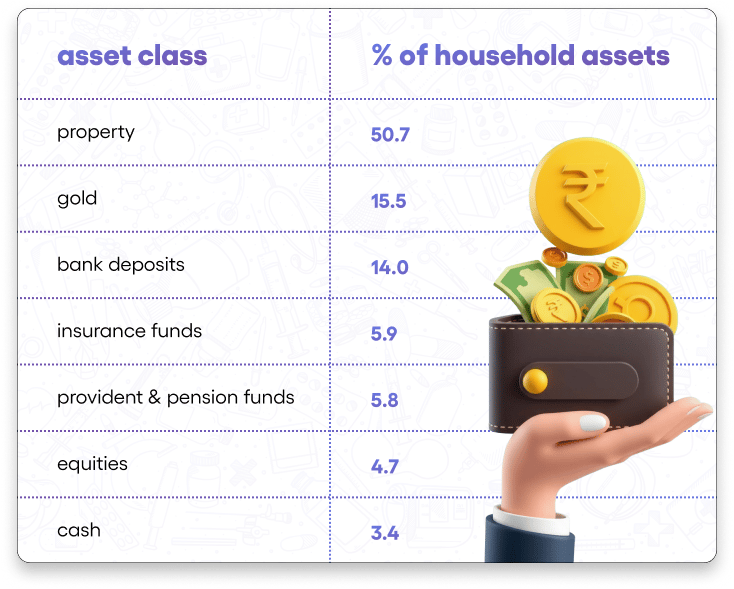

Real estate takes 51%, gold another 15%. Compare that to America's wealthiest 1%, who hold only 13% in real estate.

We have the highest physical asset concentration globally. And it's choking capital circulation.

Last year, I watched this destroy someone I know.

His father built a textile business over 40 years. Revenue peaked at ₹80 crore annually in 2010. By 2023, it had declined to ₹25 crore.

Margins collapsed. Competitors modernized while they clung to outdated processes.

The son, who'd spent ten years at a consulting firm, proposed selling to a larger player. The offer was fair. It would give the family liquidity and the employees job security with a stable parent company.

His father refused. "I built this with my hands. I'm not selling to strangers."

Six months later, they filed for bankruptcy. Employees lost their jobs anyway. The family lost everything.

This isn't an outlier.

Only 21% of Indian family businesses have formal succession plans, despite family businesses contributing 79% of India's GDP.

In 2024 alone, Sona BLW's chairman died at 53 without a succession plan, triggering family disputes. The Modi family's ₹11,000 crore battle over Godfrey Phillips erupted. The 127-year-old Godrej Group split after four years of painful negotiation.

The most instructive case remains Reliance. When Dhirubhai Ambani died in 2002 without a succession plan, Mukesh and Anil fought for three years over a ₹1.2 lakh crore empire. The eventual split worked for Mukesh. Anil's portion filed bankruptcy in 2020.

Shareholders lost billions during the uncertainty. But the brothers couldn't let go because it wasn't about the assets. It was about identity, legacy, and the inability to imagine the empire without their personal stewardship.

The 20-year court cases destroying families

Here's the scale of damage I didn't anticipate.

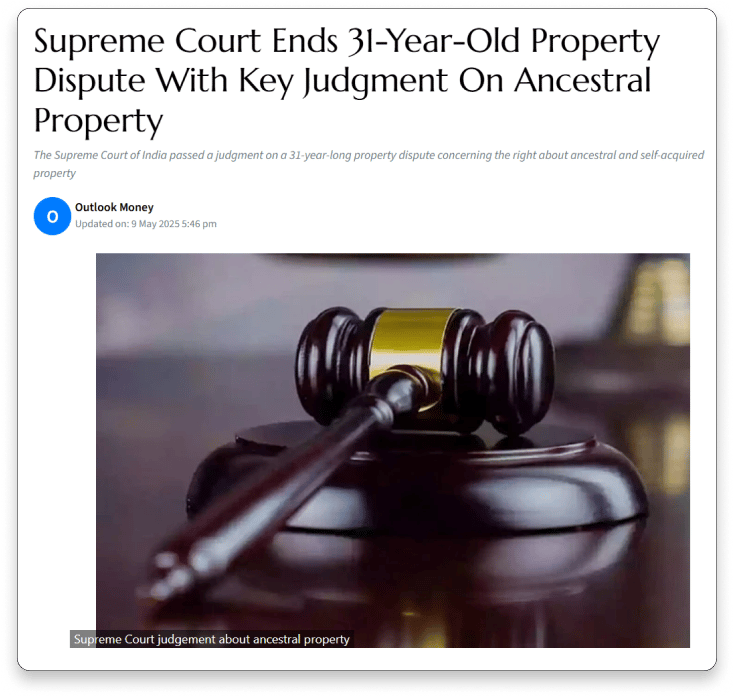

Property disputes account for 66% of all civil cases in India. A quarter of Supreme Court cases involve land conflicts.

One case resolved in April 2025 involved property purchased in 1989, disputed since 1994. That's 31 years of legal fees, family fractures, and frozen capital.

These aren't just statistics. I've seen brothers stop speaking over their father's 1,500 sq ft flat in Pune worth ₹80 lakh. The legal fees over eight years exceeded ₹12 lakh. Neither brother could use the property during litigation. Their children, who were close cousins, haven't met in a decade.

The flat sat empty. The lawyers got paid. The family destroyed itself.

Why? Because selling and splitting the proceeds felt like losing their father's legacy. So they chose mutual destruction instead.

What changed my perspective was seeing companies that overcame this.

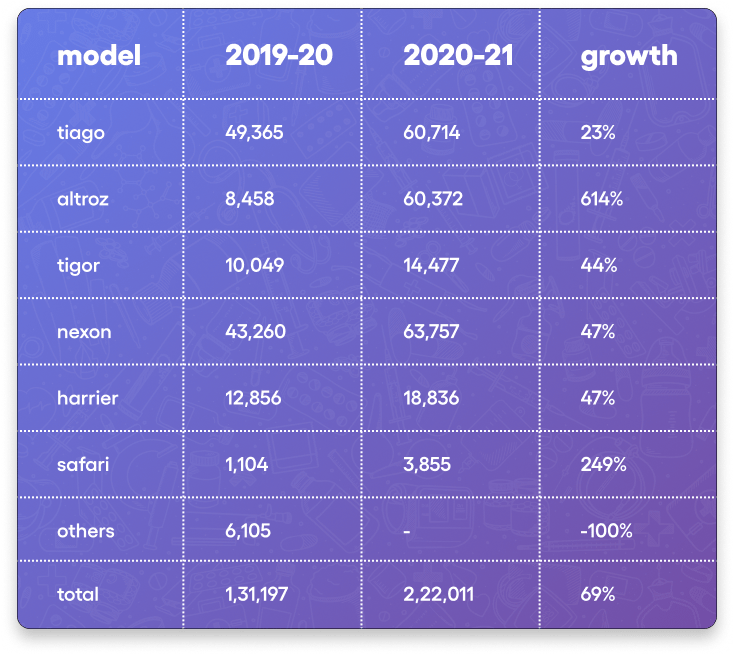

Tata Motors in 2016 was attached to legacy products. The Nano. Taxi-market vehicles. Products that defined the company's history but were killing its future. Market share had collapsed to 4.6%.

Then leadership made a brutal decision.

Exit the taxi market completely. Discontinue the Nano. Phase out the aged Safari. Launch 50+ new products targeting younger buyers.

The result? Market share surged to 8.2% by FY2021. That's 69% volume growth in a single year.

Tata Motors proved that letting go of what made you successful can be what saves you.

Policy changes work too. The 2016 RERA mandated transparency in property transactions. By forcing information into the open, it reduced the irrational valuations feeding the endowment effect. Result: residential sales reached record highs with strong growth following implementation.

The 2005 Hindu Succession Act gave daughters equal inheritance rights. Research shows this led to better child nutrition and health outcomes because women with property rights invest more in their children.

Most promising? Gen Z shows markedly weaker endowment effect. Forty-two percent work in operational roles before 30. They push digital transformation, demand formal succession planning, and view inheritance as portfolio assets, not sacred heirlooms.

My uncle still hasn't sold his Bandra property. He's now taken a third loan for medical expenses.

The property hasn't appreciated much in three years. But in his mind, selling it means betraying his father's memory. So he'll keep borrowing until either the medical bills stop or he runs out of credit.

This same psychology, replicated across millions of households and thousands of businesses, might be India's largest invisible economic cost.

The government struggles to monetize prime land. ₹160 lakh crore in gold sits idle. Family businesses fail at succession despite controlling 79% of GDP. Courts are clogged with 20-year property disputes.

None of this is about the assets' actual value. It's about our inability to separate ownership from identity.

The Japanese have a phrase for this: "mottainai." It means regret over waste. But they've built systems that prevent emotional attachment from causing that waste.

Over 90% of Japan's approximately 80,000 annual adoptions are adult men adopted specifically for business succession. Seven of the world's ten oldest companies are Japanese because they chose competence over bloodline.

India could do the same. But first, we'd need to admit that owning something doesn't make it more valuable. It just makes it harder to let go.

Until next week,

Ritesh

P.S. If you're holding onto something you can't use, can't monetize, and can't explain why you're keeping beyond "it's mine," you might be paying the endowment effect tax too. The question isn't whether the asset is valuable. The question is whether keeping it is costing you more than selling it would.